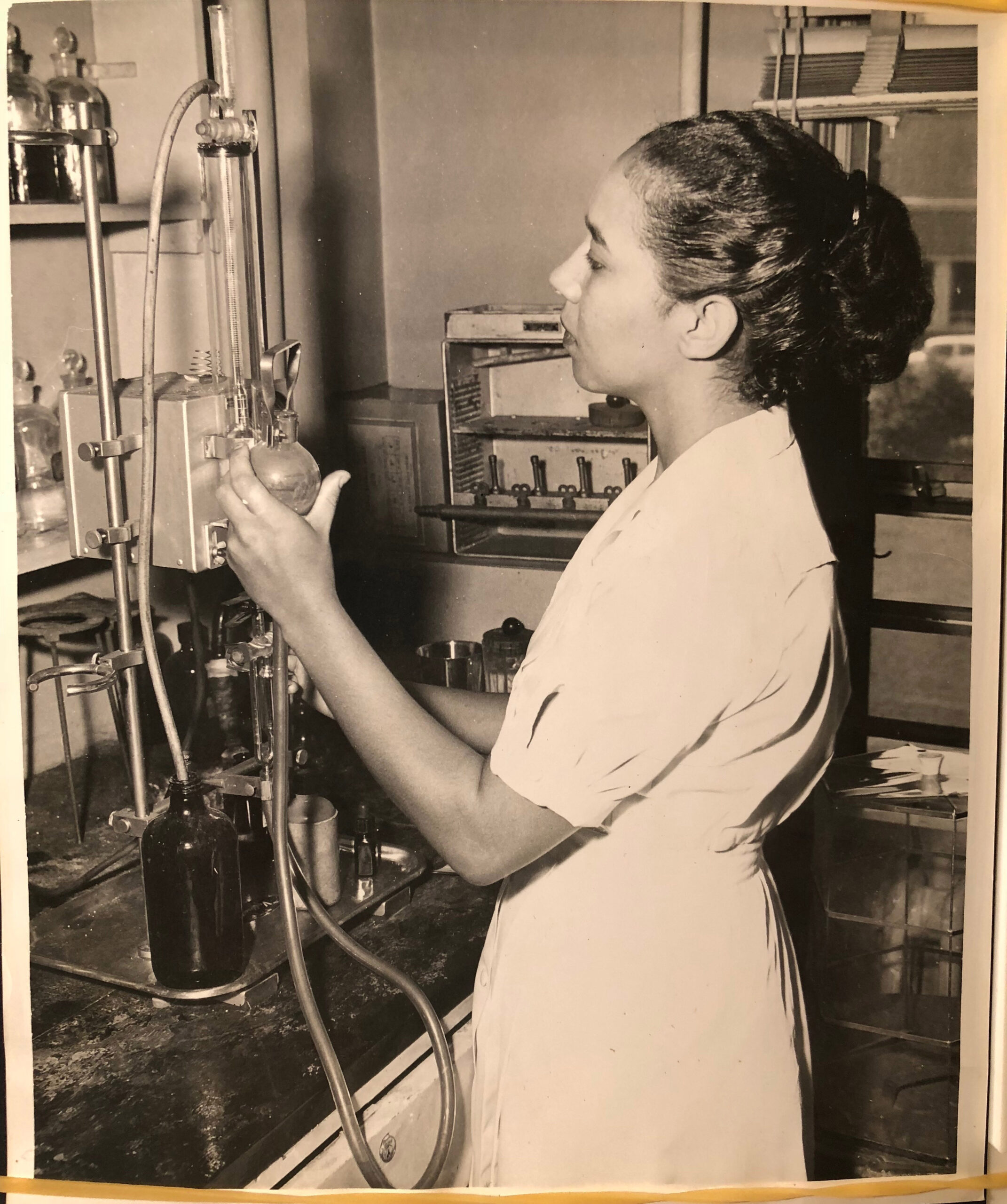

Kate Bitting Reynolds Memorial Hospital opened in 1938, and served Winston-Salem’s Black community for three decades as an essential center of medicine where doctors, nurses, hospital staff, students, and patients came together for care and education. “Katie B.,” as the community affectionately personified the institution, offered excellent and affordable health care and education, including training in all aspects of nursing and laboratory and radiological technology, which enabled many in the Black community to thrive in careers in medicine.

Though the hospital closed over a half century ago, “Katie B.” remains alive in the memories of many who trained, worked, or were cared for there, as the ongoing annual reunion of hospital staff and alumni demonstrates.

Timeline

1936

In 1936, Dr. Hobart T. Allen and officers of the Twin City Medical Society, founded by Winston-Salem’s Black physicians, confronted the mayor, demanding consideration of establishment of a hospital to care for Black patients, who at that time received hospital treatment in a separate wing of the City Memorial Hospital, where Black doctors did not have the privilege to attend their patients.

1937

Recognizing the need, Kate Gertrude Bitting Reynolds (October 4,1867 -Septemer 23,1946) left provisions in her will to establish the Kate B. Reynolds Charitable Trust, with most of the funding designated for charity patients in NC hospitals. Her husband, William B. Reynolds, donated $115,000 toward the construction of a new, 131-bed hospital in 1937.

1938

The hospital, affectionately known as “Katie B.”, officially opened on August 10, 1938 and contained state-of-the-art technology, including a fully equipped X-ray department, operating rooms, laboratory equipment for examinations and diagnosis, and a diet kitchen. The building also included an independent power system to insure that equipment would operate under adverse conditions.

The School of Nursing was established in conjunction with the hospital, training young Blacks for careers in medicine. The establishing documents indicated that the hospital and school would employ Black doctors, nurses, and teachers. In 1938, under direction of Ms. E.I. Purdie, the inaugural class of eighteen enrolled in the 3-year program, and grew to thirty-eight in the three-level program. The School received an “A” rating from North Carolina Standardization Board of Schools of Nursing.

1946

July 1, 1946, the administration of the institution came entirely under the supervision of Black personnel; for the first time, all departments were staffed by Black employees. Black doctors received full privileges in 1948. By the 1950’s, Black leaders ran all areas, including: Surgery, Obstetrics, Nursery, Gynecology, Pediatrics, Pharmacy, Radiology, Diet, Maintenance, Housekeeping, Office Management, Emergency Room and Administration.

1970

When “Katie B.” closed, the community lost the significant benefit of having a comprehensive health care facility in its midst. “Katie B.” had served as a place of healing with care provided by competent, caring professional and allied health staff. It was nationally known for its low surgical infection rate and had a stellar reputation among Black hospitals. The community had an institution of learning for many health disciplines, and a major source of pride. Experiences with “Katie B.”inspired many to pursue health care careers.

After Closure

When “Katie B.” closed in 1970, the patients moved to this location just west of the original building, which was built to serve as Reynolds Memorial Hospital. By 1972, RMC became a community clinic for medical, dental, and related services for the county’s poor, under the name Reynolds Health Center. When the Downtown Health Plaza opened, this building began to serve as the home of the Forsyth County Department of Social Services.

Reunions

Remembering their time at “Katie B,” students and faculty alike highlight the hard work, commitment to excellence, and sisterhood that marked the experience. Time at Katie B left a powerful impression on those who attended, as demonstrated by the fact that people return even now, nearly fifty years after the hospital closed, for annual reunions of those who taught, studied, and worked at the hospital.